Metamorphosis and nonhuman becomings in "Little Joe" and "The Fruit of my woman"

DEATH AS TRANSFORMATION

METAMORPHOSIS

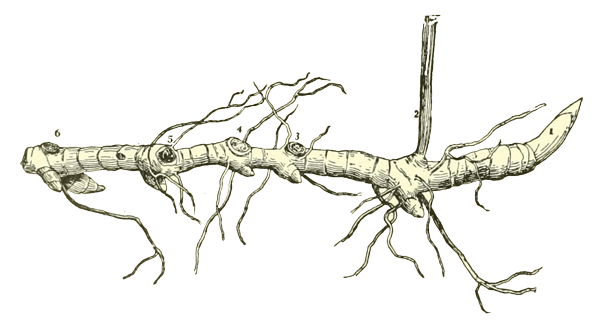

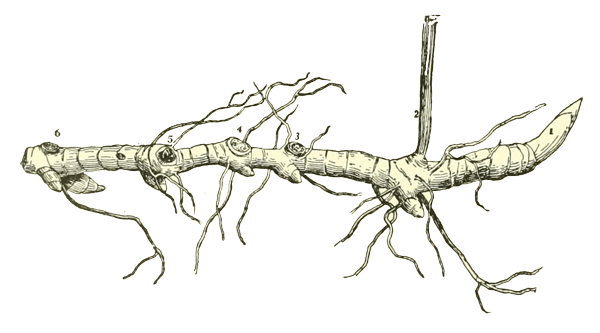

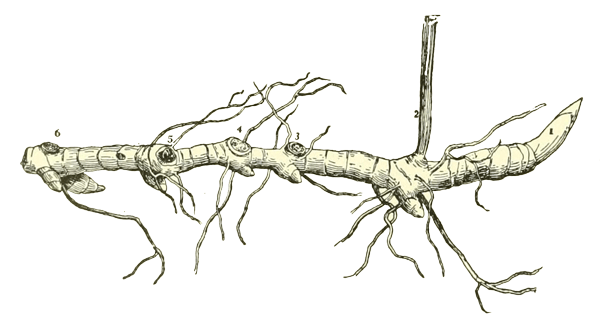

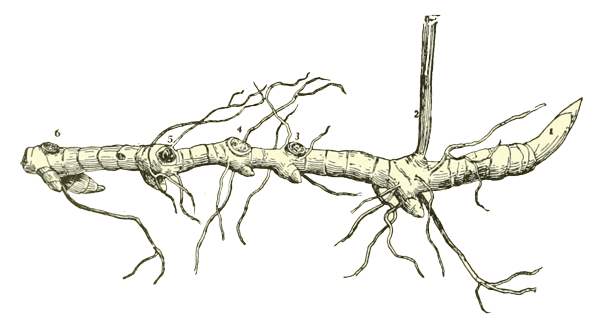

La metamorfosis no es solo un proceso que concierne a la forma global del cuerpo: también es la relación que se instaura entre las diferentes partes del cuerpo y que permite a cada una de ellas seguir una línea de vida (Coccia, 2021: 83)

Se llamó metamorfosis de las plantas al fenómeno por el cual un único y mismo órgano se presenta a nosotros bajo un gran número de formas diversas (Coccia, 2021: 84)

Toda flor es la recapitulación instantánea de la historia de un individuo vegetal: es la expresión de todo su pasado, pero también, y sobre todo, la anticipación de su futuro. La metamorfosis se presenta con una amplitud y una potencia desconocidas para lo que ocurre en los insectos. (Coccia, 2021: 87)

EXTINTION

La metamorfosis no es solo un proceso que concierne a la forma global del cuerpo: también es la relación que se instaura entre las diferentes partes del cuerpo y que permite a cada una de ellas seguir una línea de vida (Coccia, 2021: 83)

Se llamó metamorfosis de las plantas al fenómeno por el cual un único y mismo órgano se presenta a nosotros bajo un gran número de formas diversas (Coccia, 2021: 84)

Toda flor es la recapitulación instantánea de la historia de un individuo vegetal: es la expresión de todo su pasado, pero también, y sobre todo, la anticipación de su futuro. La metamorfosis se presenta con una amplitud y una potencia desconocidas para lo que ocurre en los insectos. (Coccia, 2021: 87)

“Esto es, uno podría —como el mundo después de la teoría debe obligarnos a hacer— considerar

sobre qué superviviencia vale la pena preocuparse, qué de lo humano, de la multitud o de lo vivo haría posible un ethos que no fuera el ethos del presente”.

Claire Colebrook. “Extinción de la teoría”. Revista de Filosofía · año 51 · núm. 146 · enero-junio 2019. p64

Woman-(m)other &

the Monstrous-feminine

MEDITACION VEGETATIVA ENRAIZADORA

«One of the most common forms of denial of women and nature is what I will term backgrounding, their treatment as providing the background to a dominant foreground sphere of recognised achievement or causation. This background of women and nature is deeply embedded in the rationality of the economic system and in the structures of contemporary society. What is involved in the backgrounding of nature is the denial of dependence on biospheric processes, and a view of humans as apart, outside of nature, which is treated as a limitless provider without needs of its own» (Plumwood, 2003: 21).

«The presence of the monstrous-feminine in the popular horror film speaks to us more about male fears than about female desire or feminine subjectivity. However, this presence does challenge the view that the male spectator is almost always situated in an active, sadistic position and the female spectator in a passive, masochistic one» (Creed, 2007: 21).

«[…] situating the monstrous feminine in the horror film in relation to the maternal figure and what Kristeva terms ‘abjection’, that which does not ‘respect borders, positions, rules’, that which ‘disturbs identity, system, order’ (Kristeva, 1982, 4)» (Creed, 2007: 23).

«The mother herself is background and is defined in relation to her child or its father (Irigaray 1982), just as nature is defined in relation to the human as ‘the environment’. […] So the mother's product —paradigmatically the male child— defines his masculine identity in opposition to the mother's being, and especially her nurturance […]. He resists the recognition of dependence, but continues to conceptually order his world in terms of a male (and truly human) sphere of free activity taking place against a female (and natural) background of necessity» (Plumwood, 2003: 22).

«[…] or the monstrous is produced at the border which separates those who take up their proper gender roles from those who do not» (Creed, 2007: 26).

The Fruit of my Woman (1997) - Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith (2016)

«My wife avoided my gaze like a child caught doing something wrong. Slightly regretting having seemed to scold her, I made an effort to soften my tone» (pt. 1).

«Her wet, blotchy face was unsightly. As my splayed fingers ran through my wife’s brittle hair, I gave her a toothy smile. ‘And do be careful how you go. You don’t want to be hurting yourself again. It’s not as though you’re a child, to be falling over and bumping into things.’» (pt. 2)

«Mother.

I’m not able to write you letters anymore. Or to wear the sweater you left here. That orange woollen sweater, the one you accidentally left behind when you came up to visit last winter.

I wore it the day after he went on his business trip. You know how I feel the cold.

It hadn’t been washed, so it still had that smell of stale side dishes mixed in with the scent of your skin. On a different day I probably would have washed it, but it was too cold, and besides, I wanted to keep breathing in that scent, so I kept it on, and even fell asleep wearing it. The next morning, the frost still hadn’t relaxed its grip, and perhaps it was because I was so cold and thirsty that, when the morning sunlight eventually shone through the bedroom window, that stifled cry broke out from me: mother. Wanting to be enfolded in that warm light, I went out onto the balcony and took off my clothes. The sun’s rays penetrating my bared flesh were so much like your scent, I knelt there and called out mother, mother. No other words.

I wonder how much time passed. Days, weeks, months? Having noticed that the air didn’t seem particularly warm, all I registered after that was a slight rise in temperature, followed by a comparable dip.

Any moment now, the windows of the distant flats over the Chungnang stream will blaze with an orange light.

Can the people who live there see me? What about the cars that race along the main road, light streaming from their headlights? What do I look like now?» (part 7)

x x x

«That poor village by the sea was your whole world. You were born there and grew up there. You gave birth there, worked there, grew old there.

At some point, you will be laid there at the foot of our family burial ground, side by side with father.

It was fear of ending up like you, mother, that made me put such a distance between myself and my home. Leaving home at seventeen, the urban districts of Busan, Daegu, Gangneung, where I wandered aimlessly for over a month, have remained in my memory.» (part 7)

x x x

«Now, her form retains barely a trace of the biped she once was. Her pupils, which seemed to have metamorphosed into shining round grapes, are gradually being buried in brown stems. My wife cannot see anymore. She can’t even flex the ends of the stems. But when I go out onto the balcony I feel a hazy sensation that defeats all language, like a minute electric current pulsing out from her body and into mine. When the leaves which were once my wife’s hands and hair all fell out, and the place where her lips had meshed together split open, releasing a handful of fruit, that sensation ended like a thin thread snapping.

The tiny fruits had burst out en masse like pomegranates; I gathered them in my hands and sat down across the threshold that connects the balcony to the living room. These fruits, which I was seeing for the first time, were a yellowish green. And they were hard, like the sunflower seeds they serve alongside popcorn as an accompaniment to beer.

I picked out one and popped it into my mouth. The smooth rind was entirely devoid of taste or smell. I crunched down on it. Fruit of the only woman I’d ever had on this earth. The first thing my palate picked up was an acidic, almost burning flavour, and the juice that clung to the root of my tongue had a solely bitter aftertaste.

The next day I bought a dozen small, round flowerpots, and after filling them with fertile soil, planted the fruits in them. I lined the small flowerpots up next to that of my withered wife, and opened the window. I leant out over the railing and smoked a cigarette, savouring the smell of fresh grass that had suddenly bloomed from my wife’s lower parts. The chill wind of late autumn ruffled my cigarette smoke, my long hair.

When spring came, would my wife sprout again? Would her flowers bloom red? I just didn’t know.» (part 8)

Irigaray urges us to learn from plants and their modes ofbeing in the world, including a focus on becoming, rather than being, a relativization of preassigned roles and a nonappropriative relation to one's surroundings. (Glagliano, Ryan, Vieira, 2017)

First she dies. Then she loves.

I am dead. There is an abyss. The leap. That Someone takes. Then a gestation of self~in itself, atrocious. When the flesh tears, writhes, rips apart, decomposes, revives, recognizes itself as a newly bom woman, there is suffering that no text is gentle or powerful enough to accompany with a song. Which is why, while she's dying-then being bom~silence. (Helene Cixous, Coming to Writing, 36)

The questor's awakening takes place when she comes to realize that she is no longer compatible with the terms of her former existence-that her self-conception no longer compatible with the gender role forced upon her by society. The metamorphosis mofif defines the heroine's quest. If successftil, it enables her to utilize the material of her imprisonment, language, to escape the cocoon as a mature creature able to successfully propagate her own kind.

If she is successful in that re-definition, she transforms the world from a hostile environment into one that accommodates her as the complete creature—the newly born woman. (Allen, 1997: 8)

‘I want to go and get some new blood in my veins,’ she said. This was the evening of the day when she’d finally given her letter of resignation to her immediate superior. She told me she wanted to transfuse the bad blood that was clotting up her veins like cysts and flush out her tired old lungs with fresh air. Living and dying freely had been her dream ever since she was a child, she said (Kang, 1997)

"James Lovelock, for example, has argued written that we have reached a point where simply being more green will not suffice; only more technology will save us (Aitkenhead 2008). But who is this ‘we’ that has reached a tipping point and has declared ‘game over’? And who is this ‘we’ that declares that only the technology that got ‘us’ into this mess will help us into the future? The threatened ‘we’ of techno-science finds nothing more alarming than the possible end or non-being of techno-science, even as it acknowledges that techno-science has been the motor of destruction. The Cartesian echo of ‘I face extinction therefore I must continue to be,’ alerts us to the modernity and hyper-humanism of the logics of extinction. It is only with a radical separation of thinking as a substance, and not (as it was prior to Descartes) a potentiality of ensouled life, that the possibility of the erasure of thought becomes thinkable.

(...)

What if rather than focusing on extinction, or on how many species we are losing and how we may lose ourselves, one looked at all the ways in which what has come to recognise itself as the species of humanity already required the extinction of other ways of being human? If there were no logic of species then one might problematise humans as a whole; one might think of extinction not as the erasure of thinking but as an opportunity to ask about what is worth saving, and – more importantly – about whether one might imagine a world in which ‘saving’ is not the only ethical comportment towards future life".

Claire Colebrook. "Extintion", In Braidotti, Rossi y Maria Hlavajova. Posthuman Glossary. Bloomsbury Academic. (2018).

ANTROPOCENO O PLANTACIONOCENO?

Para seguir pensando

Parte de para la comunidad científica ha convenido en llamar a la era geológica actual Antropoceno, desde el entendido que la sexta extinción masiva del Holoceno es un fenómeno en curso provocado por la fuerza geomórfica de la actividad humana a escala planetaria.

Sin embargo, para algunxs autores, el concepto de Antropoceno limita las posibilidades de comprender las causas de la crisis ecosocial en curso, y por lo tanto, de pensar las posibilidades de respuesta ante la misma.

Lo que sigue son algunos extractos de una conversación que Donna Haraway y Anna Tsing mantuvieron con Gregg Mitman en la que discuten los alcances y limitaciones del término y lo comparan con la noción de Pantacionoceno como categoría posible para pensar la era actual desde un punto de vista que ponga el foco en la responsabilidad de determinadas formas de vida humanas en la crisis ecosocial.

Gran parte del trabajo de ambas, trata sobre pensar en el florecimiento multiespecie, aún en plantaciones y paisajes perturbados, lo que trae a la conversación la pregunta acerca de la importancia de pensar con otras formas de vida no humanas, y las posibilidades que eso crea para pensar en futuros alternativos.